The People Who Show Up: Clallam County’s Safety Net in Action

Part Two of a Six-Part Series — inside the work of shelters, outreach teams, behavioral health providers, and law enforcement who refuse to give up.

Welcome back, I’m so glad you’re on this journey as we grapple with such an important issue facing our community. In the last article in this series on homelessness in Port Angeles, we mapped the landscape of homelessness in Clallam County—the scope, who is most affected, and the pressures driving instability. To see the human side more clearly, I began with a two-hour group interview with four local leaders: Joe DeScala (4PA), Sharon Maggard (Serenity House), Wendy Sisk (Peninsula Behavioral Health), and Chief Brian Smith (Port Angeles Police Department). Two hours only scratched the surface.

That conversation led to hours of follow-up interviews and a deeper dive into local data. Their voices, and the statistics that frame them, will unfold across this series.

This piece turns to the helpers. Across Clallam County, front-line teams face work that can feel overwhelming. They show up anyway—not because they can end homelessness overnight, but because every shelter bed, every meal, and every link to care matters. Sometimes their views overlap; sometimes they diverge. Taken together, they reveal what it means to be “on the front lines”—imperfect, candid, collaborative—and why, without them, the situation would be far worse.

Joe DeScala and 4PA: A Grassroots Voice

For Joe DeScala, founder of 4PA, addressing homelessness and addiction starts with presence—being visible, accountable, and practical in the places where help is needed most. 4PA—short for For Port Angeles—is a grassroots nonprofit that brings volunteers together to support public safety, respond to community needs, and create pathways for people ready to turn their lives around. If you’d like a fuller introduction to their work, I’ve profiled the organization previously in Touchstone of Change: Local Non-Profit 4PA Steps Into the Arena on Clallam County Solutions.

4PA began with something simple: community cleanups. Volunteers rolled up their sleeves, picking up garbage and abandoned items in public spaces, not just to beautify the town but to restore a sense of safety and care for shared spaces. From there, the group evolved. What started as cleanup efforts grew into a larger vision: creating a place where those in need could find refuge from the weather, safety from the streets, and an opportunity to gain skills that would help them move further from homelessness and closer to stability.

In the broader system of organizations addressing homelessness, 4PA fills a distinct role: providing a “high barrier” model of support. Their program requires sobriety for those who wish to engage with their services. For some, that line is controversial, but for Joe it is a matter of compassion grounded in realism: without sobriety, stability cannot last. 4PA offers people a safe environment, job training opportunities, and a structured community designed to help them transition into more secure, long-term housing.

This perspective also shapes how Joe talks about the crisis. He is candid about what he sees as the central role of addiction—and especially fentanyl—in driving instability and crime. Chief Smith chimed in, “There’s no property crime here that isn’t related to substance use. If you wanted to centralize your crime conversation, you’d talk about fentanyl—the people who sell it, the people who are dealing it, and the people who steal for it. That’s a much more accurate conversation than tying homelessness to crime.” His point, shared by Joe, is not to stigmatize but to insist on honesty: without naming fentanyl as a driver, it is impossible to respond effectively.

Local data backs this up. In 2024, Port Angeles police recorded 430 larceny/theft offenses, 241 cases of property destruction, and 208 burglaries. Drug crimes showed a similar pattern: more than half involved “other drugs,” a category that includes fentanyl, with stimulants making up nearly a third. Overall, a property crime was reported in the city roughly every two minutes.

At the same time, Joe resists reducing homelessness to a single cause. “Homelessness can cover a broad spectrum of people, but that essence of having that stable place of dwelling is kind of what I go by. A tent doesn’t constitute that. Couch surfing doesn’t constitute that. It’s more than that.” For him, the measure of success is not temporary relief but stability—the kind of housing and support that allows people to rebuild their lives.

That combination—realism about the devastation of addiction, insistence on stability through sobriety, and optimism about the community’s ability to face hard truths together—is what defines both Joe and 4PA. They do not promise easy answers. But in their visibility, their boundaries, and their willingness to show up day after day, they offer Port Angeles something vital: a model of grassroots engagement that refuses to give up on either honesty or hope.

Sharon Maggard and Serenity House: The First Rung of Emergency Shelter

If there is a cornerstone in Clallam County’s homelessness response, it is Serenity House. Under the leadership of Executive Director Sharon Maggard, Serenity House has become the second largest housing and shelter provider in the county (behind only the Peninsula Housing Authority), serving thousands of people every year. Where other organizations fill specialized roles, Serenity House anchors the system: providing food, safety, warmth, and a first step toward stability for those with nowhere else to go.

In the spectrum of homelessness services, Serenity House occupies the emergency and transitional housing lane. It is the place people go when their options have run out—families facing eviction, youth aging out of foster care, adults sleeping outside in the cold. The Port Angeles adult shelter alone provided more than 35,000 bed nights to 634 unique guests in the past year, while its kitchen served more than 52,000 meals. Beyond that, Serenity House’s programs supported more than 3,200 households countywide, from rental assistance to transitional housing (per the organization’s most recent annual report).

The decision to take on this role was deliberate. For Sharon, the first step in recovery and stability is ensuring that people are safe tonight—fed, warm, and sheltered. “The causes for homelessness could be anything—I could have lost my job, lost a spouse, had a huge medical bill, or been in a domestic violence situation where it wasn’t safe to go back home. For some people it is addiction, but for many it’s just ugly life circumstances. I even have people in my shelter who go to work every day but still can’t find an apartment they can afford.”

At the same time, Sharon is frank about the hardest cases. A significant share of those who come through Serenity House are not just facing a temporary setback, but are caught in generational cycles of addiction and trauma. “At any of our agencies, there can be grandparents, parents, children, and even great-grandchildren in systems of care. The cycle of substance use and physical or mental trauma becomes an environmental structure in some households, and those are often our hardest cases to help.” These are the individuals and families who require long-term, trauma-informed care to break the patterns that have persisted for decades.

Why choose this lane, knowing it comes with such challenges? For Sharon, the answer is simple: because without emergency shelter, people die on the streets. Serenity House is often the front door of the system, the first place someone turns when they lose housing. By catching people at that moment of crisis, Serenity House prevents deeper harm and creates at least the possibility of moving forward—whether into transitional housing, supportive services, or eventually permanent housing.

“It isn’t our goal at all to put people back out on the street. We want them to move into our apartments and stay there, and if they get a job and move, more power to them. But we really don’t have those people. The people we serve need stability, and our role is to give them a safe place for as long as they need it.”

The scale of the work is enormous, and the strain is real. Beds are full, the waiting list for affordable housing in Clallam County exceeded 2,400 people as of mid-2024, and staff are stretched thin. Yet Serenity House continues to show up. Each bed night, each meal, each youth reached through its programs represents someone who is not entirely alone in their struggle.

In the spectrum of solutions, Serenity House is the first rung: the place where people land when everything else has failed. Its role is not glamorous, and the challenges can feel overwhelming. But Sharon’s leadership reflects a steady mix of realism and compassion—the recognition that while no shelter can solve homelessness on its own, ensuring that no one is left completely without support is itself a vital part of the solution.

Wendy Sisk and Peninsula Behavioral Health: Meeting Behavioral Health Needs

Homelessness is not only a housing issue. In Clallam County, as in many rural communities, untreated mental illness and substance use disorders play a central role in who becomes unhoused and who struggles to find stability once they are. That is where Peninsula Behavioral Health (PBH), led by CEO Wendy Sisk, steps in. PBH is the largest provider of mental health and addiction treatment services in the county, making it a critical part of the safety net.

In the spectrum of organizations responding to homelessness, PBH fills the mental health and recovery role. Shelters can provide safety, and grassroots groups like 4PA can offer community and structure, but PBH provides the clinical and therapeutic services that help people stabilize their lives. Their focus is not only on crisis response, but also on long-term treatment and recovery—areas that, if left unaddressed, leave many people cycling between homelessness, jail, and hospitals.

One of the most important things PBH has built into its system is immediate access. As Wendy explained, “We do not have long wait times for treatment. We actually have walk-in access [at least once weekly] to get people started in care.” That kind of access is essential when someone in crisis makes the decision to reach out for help—delaying intake by weeks or months can mean losing that opportunity altogether.

Still, Wendy is quick to acknowledge the limits. Detox services, inpatient treatment programs, and supportive housing units are stretched thin, with far more demand than supply. It is one thing to get someone started in care quickly; it is another to keep them in recovery when long-term resources are lacking. That gap is not for lack of effort, but because Clallam County faces the same challenges seen nationwide: too few treatment beds, workforce shortages, and a rising tide of need.

“A roof doesn’t always solve everything. Some people have been homeless so long that even when they get housing, it takes time to relearn how to feel safe and how to take care of themselves again.”

Why does PBH take on this difficult role? Because, as Wendy and her team know, mental health and addiction are among the most powerful drivers of homelessness. Without treatment, stability is almost impossible to sustain. With treatment, the path forward—even if slow and uneven—becomes possible. PBH’s role is to make sure that path exists.

The impact is seen not only in individual recoveries but also in how PBH partners with other agencies. Their clinicians work with Serenity House to stabilize shelter guests, with law enforcement when someone in crisis is taken into custody, and with hospitals to ensure people leaving medical care are not discharged back to the streets. In each case, PBH provides the behavioral health expertise that no other local organization can.

Wendy’s leadership is marked by clarity and balance: she recognizes the limits of what PBH can do, but she is committed to ensuring that treatment remains available and accessible for those who seek it. In the wider safety net, PBH plays a unique role. It does not provide shelter beds or meals, but it addresses the underlying behavioral health needs that so often stand between people and long-term housing stability.

Chief Brian Smith and the Port Angeles Police Department: Public Safety in Balance

The Port Angeles Police Department is not a housing provider, a shelter, or a treatment agency. Yet homelessness inevitably intersects with public safety, making law enforcement an unavoidable part of the community’s response. For Chief Brian Smith, the role of the police is clear: to maintain public order, respond to crime, and deal with the visible impacts of addiction and homelessness. In the spectrum of organizations addressing this crisis, PAPD occupies the public safety and community order role.

Chief Smith is quick to emphasize that homelessness and crime are not the same thing. Most people experiencing homelessness in Port Angeles are not criminals, and he cautions against broad assumptions. “I wouldn’t tie the percentage of crime we have to people who are unhoused… they’re not the driver of our crime. There are people within that population that commit a crime, but the driver of our crime is people that commit the crime, and they’re generally not the people [who are homeless].”

The data bears that out. In 2024, Port Angeles police recorded 1,595 total offenses, including 259 simple assaults and 314 weapons-related incidents. Drug crimes, while highly visible, made up just 199 cases. For Chief Smith, that underscores his point: the unhoused population is not driving crime overall, even as substance use shapes many of the calls his officers respond to.

At the same time, Smith does not minimize the impact of substance use. Addiction, he says, is where the overlap lies. Over the past decade, fentanyl has transformed the landscape of both public safety and homelessness. “Notable changes… ten years ago, heroin was a problem, methamphetamine was a problem, fentanyl had just sort of emerged. Fast forward, fentanyl is more damaging, more destructive, more addictive—probably the most addictive drug ever known in human history—and it’s everywhere. [Certainly an element of the] unhoused population here is really affected by substance use.”

Taken together, these two perspectives form the core of Smith’s message: being unhoused does not make someone a criminal, but the rise of fentanyl has pulled many vulnerable people into cycles of instability that spill over into public safety. For police, that means walking a fine line—holding accountable those who commit crimes, while also recognizing that addiction and poverty are often the underlying drivers.

That’s why PAPD leans on coordinated responses—pairing enforcement with handoffs to shelter, treatment, or medical care whenever possible. Balancing compassion with accountability is one of the hardest parts of the job. Officers are often placed in situations that stretch far beyond traditional law enforcement. They find themselves acting as social workers, health responders, or even mediators, navigating the blurred lines between public safety and human crisis. For Chief Smith, this underscores why partnerships matter. The police cannot—and should not—be the sole response to homelessness.

“It’s more about how you behave towards others. That’s how you have partnerships—it’s how you treat people and how you interact. Partnerships occur organically among people who are willing to be honest, ethical, and reliable.”

PAPD regularly collaborates with organizations like Serenity House, Peninsula Behavioral Health, and grassroots groups like 4PA. Officers transport people in crisis to shelters, connect them with detox or treatment when beds are available, and coordinate with outreach teams. In many cases, the police are the first point of contact when someone is in danger, and their actions can make the difference between a night in jail, a night in the ER, or a night in shelter.

The strain is real. Property crimes make up more than half of reported offenses in Port Angeles, and substance use is frequently a factor. Officers respond again and again to the same calls, often involving the same individuals. Without PAPD’s involvement, community safety and order would deteriorate further. But Smith is clear: policing alone cannot solve homelessness. It can only manage its public safety impacts while other systems—shelters, treatment providers, housing programs—do their part.

In the broader spectrum of solutions, Chief Smith positions PAPD’s role as both limited and essential. The police cannot build housing or provide treatment, but they can enforce accountability, reassure residents and businesses, and partner with service providers to redirect people toward help. His leadership emphasizes clarity: fentanyl is the real driver of much of the crime, and any effective response must combine accountability with compassion, law enforcement with collaboration.

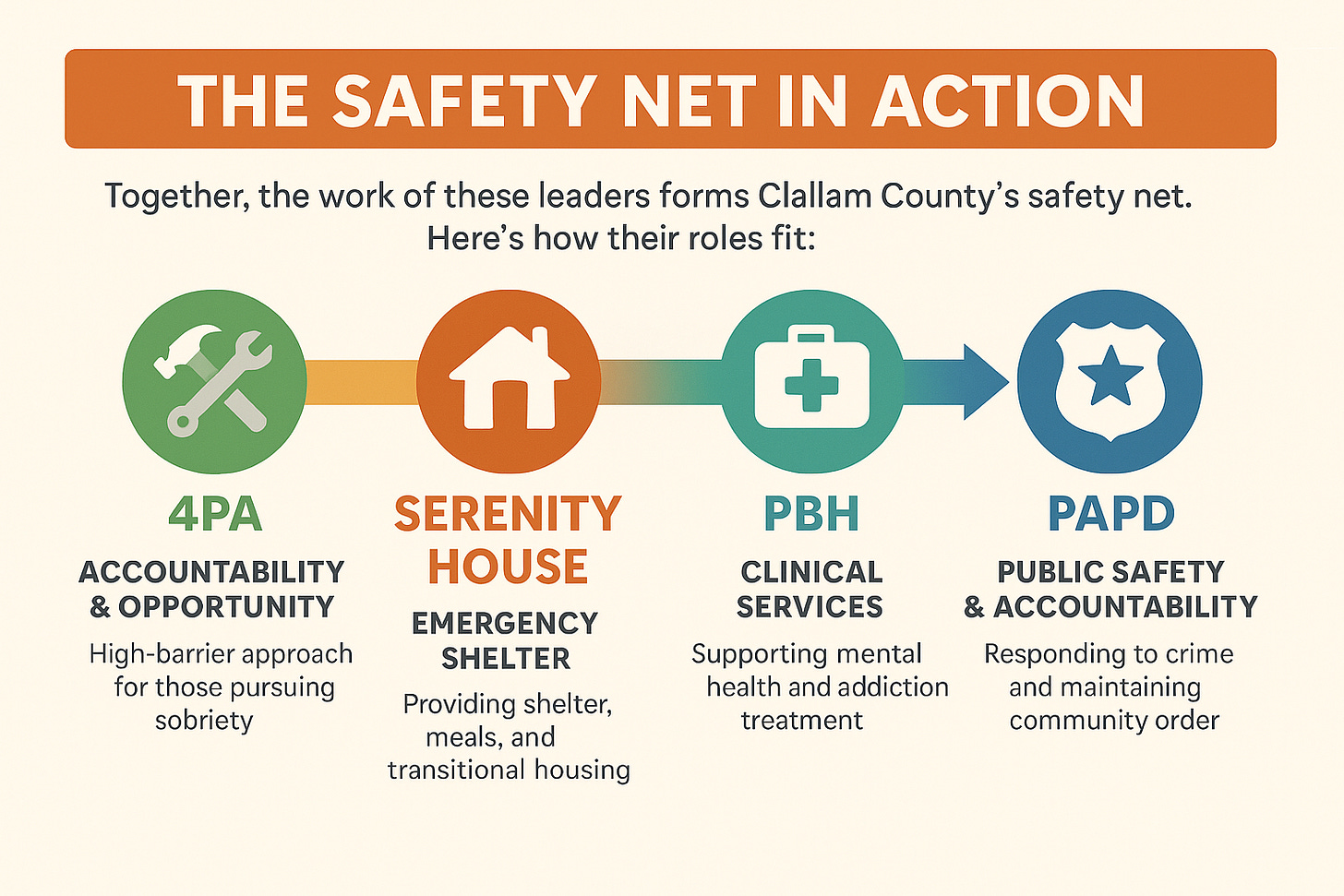

The Safety Net in Action

Together, the work of these leaders forms Clallam County’s safety net. Here’s how their roles fit:

Joe DeScala and 4PA focus on accountability, structure, and opportunity for those ready to pursue sobriety. Their high-barrier approach creates a safe space for people to take tangible steps forward, building skills and preparing for more permanent housing.

Sharon Maggard and Serenity House anchor the emergency side of the spectrum—providing shelter beds, meals, and transitional housing for thousands of people each year. Their work ensures that no one is left without food, warmth, or a starting point, even when long-term solutions remain out of reach.

Wendy Sisk and Peninsula Behavioral Health address the clinical needs that underlie so much of the crisis: untreated mental illness and substance use disorders. PBH provides immediate access to care and strives to offer longer-term treatment and recovery, even within the limits of rural resources.

Chief Brian Smith and the Port Angeles Police Department play the role of public safety and accountability. Their officers respond to crime, maintain community order, and partner with service providers to redirect people in crisis toward help when possible.

Individually, each of these leaders would admit their work is not enough. But together, their organizations form a safety net that keeps countless people from falling further. Shelters prevent deaths on the street, treatment stabilizes lives in crisis, high-barrier housing offers structure and hope, and law enforcement manages the public safety impacts that ripple through neighborhoods.

The system is far from perfect, and the net often feels stretched to the breaking point. Yet without these efforts, Clallam County would face a far harsher reality. Their persistence doesn’t solve everything—but it proves our community hasn’t given up.

Collaboration and Common Ground

One of the most striking parts of bringing these four leaders together was how often they emphasized collaboration. Despite representing very different roles—grassroots outreach, shelters, behavioral health, and law enforcement—what stood out in the group interview was their respect for one another and their shared belief that working together is essential.

Chief Brian Smith described it plainly: “We work really well together. We respect each other. I will defend any one of these people and what they’re doing… we support each other, we appreciate each other, and we don’t expect each other to do things exactly the same way.”

For Sharon Maggard, the benefits of partnership have been measurable. She noted that stronger collaboration—particularly between Serenity House and the police department—has directly reduced strain on services. “I really think our strengthened partnerships over the last four years—and certainly working with the police department—[mean] our [police calls and service contacts] have almost halved. I think our ability to support each other is the reason.”

Wendy Sisk echoed that reflection, noting how far things have come since she first stepped into her role at Peninsula Behavioral Health. “One of the nice things about the group of providers in our community that are working… is that collaboration. I don’t think that’s always the case. And really, it wasn’t the case when I first took over this position.”

Sharon Maggard, who came out of a career at Intel before moving into nonprofit leadership, described a mindset she carries forward: the ability to commit to collaboration even when there are differences. “ The first thing you learn there is how to disagree and commit. I may disagree with you 100%, but if all of you say that’s where we’re going, I will commit 100% to help you go in that direction.” Wendy Sisk agreed with the sentiment, noting that even though her background is rooted in behavioral health, the principle resonates strongly in the way local providers now work together.

Taken together, these reflections show that the safety net in Clallam County is not just a patchwork of separate organizations. It is a web of partnerships, strengthened by leaders who trust one another and choose collaboration over competition. That willingness to work together—even when their methods or philosophies differ—is one of the clearest sources of hope in an otherwise difficult landscape.

Conclusion: The Helpers in Context

It would be easy to look at these stories and see only the hope: volunteers showing up in bright vests, shelters serving thousands of meals, clinicians opening their doors, and police officers working alongside service providers. And in truth, there is a great deal of hope here. These leaders and their teams are proving every day that compassion, persistence, and collaboration can make a difference.

But to stop there would be incomplete. None of these organizations would claim that their work is without flaws, or that the challenges are simple. Each faces limits—whether it is too few treatment beds, shelters stretched to capacity, staff under pressure, or the frustrations of dealing with repeat offenders. They know better than anyone that progress is often slow, uneven, and difficult.

Some readers may be tempted to say that this paints too rosy a picture, or that it overlooks problems within these systems. The reality is that both are true: there is good work happening, and there are serious challenges still to confront. To ignore either side would be misleading. What this article has aimed to show is that Clallam County has people in the arena—leaders who refuse to turn away and who, despite imperfections, are holding the line against a crisis that would be far worse without them.

In the next installment, we’ll turn directly to those challenges. We’ll look at what isn’t working: the barriers of limited funding and service capacity, the weight of staff burnout, and the misconceptions that shape public perception. We’ll hear from these same leaders about the realities that make this work so difficult—and why acknowledging those realities is essential if we want real solutions.

Holding both truths—the work being done and the barriers that remain—is how we move forward with the honesty and persistence this issue demands.

I hope you’ll join me as we continue on this journey!

Active dialogue and engagement with our readers is crucial. Writers on this platform are encouraged—and expected—to revisit their articles regularly, responding thoughtfully to readers’ questions and concerns.

We want conversations, not shouting matches. Therefore, comments will be reviewed regularly and are expected to adhere to these foundational guidelines:

Stay on Topic: Comments must relate directly to the article.

Respectfulness: Every comment should demonstrate respect toward authors, website management, and fellow commenters. Bullying, name-calling, or disrespectful behaviors will not be tolerated.

Constructive Dialogue: Political grandstanding is unwelcome here. While some discussions naturally involve political elements, the goal is to enhance understanding, clarify perspectives, and contribute constructively.

No Personal Attacks: As Theodore Roosevelt wisely said, it's the person who is "actually in the arena" who deserves our respect. Criticism is welcome, but personal attacks are not.

Transparency: Any new guidelines needed as this platform evolves will prioritize civility, decency, and productive dialogue.

This is an excellent article. Every person in PA and Clallam County should read this. There are so many misconceptions about the homeless. It takes articles like this to open people's eyes. As a father of 3 adopted children who have all experienced homelessness, I commend you.

Thanks for writing this up. One of the most shocking data points I heard was from Chief Smith. He said we can’t trust the crime statistics in Port Angeles because we have a very low ratio of officers per capita. I think he said we run at half the ratio of other states. His conclusion was that if he had MORE officers, we would have HIGHER crime statistics. That just proves the level of lawlessness not addressed or unreported in our community. It also matches a theme that Prosecutor Nichols suggested when he hinted many citizens have lost faith in the system and increasingly don’t even call to report crimes. This level of futility scares me - yet with unreliable statistics, I don’t even know how fearful I should be. How will we ever really know if things are getting better or worse?