The Realities of Homelessness in Port Angeles: A Community in Context

Part one of a six-part series examining homelessness in Port Angeles: who is affected, what the numbers show, and the pressures shaping this crisis.

Homelessness is one of the most visible and pressing challenges in Port Angeles and across Clallam County. It’s a subject that often sparks strong emotions, from frustration and fear to compassion and determination. What’s clear is that no single story—or single solution—can capture the full scope of this complex issue.

When I began this project, I originally envisioned writing a single article. But after hours of interviews with local leaders, and digging through detailed data from Serenity House and the Port Angeles Police Department, I quickly realized that an issue as complex and nuanced as homelessness in our community deserved more space. To truly explore the challenges, the human stories, and the solutions being pursued, it needed to become a series.

This first article sets the foundation by taking a clear-eyed look at the landscape of homelessness in Port Angeles: who is affected, what the numbers reveal, and the root causes that drive instability. In the coming articles, we’ll turn to the helpers working on the front lines, examine the obstacles within our systems, take a closer look at public safety and substance use, explore cycles of trauma and addiction, and finally, highlight the solutions and community efforts pointing the way forward.

This is not an easy subject, but it is one where honesty and hope must walk together. By understanding the landscape, we can better appreciate the work already underway—and prepare ourselves to imagine what comes next.

The Spectrum of Homelessness — and What the Numbers Reveal

Homelessness in Clallam County is not a single experience—it exists on a wide spectrum. Some people lose housing suddenly because of a medical bill, a job loss, or a family crisis. Others face chronic struggles tied to addiction, mental illness, or disability that make it difficult to maintain stable housing without long-term support.

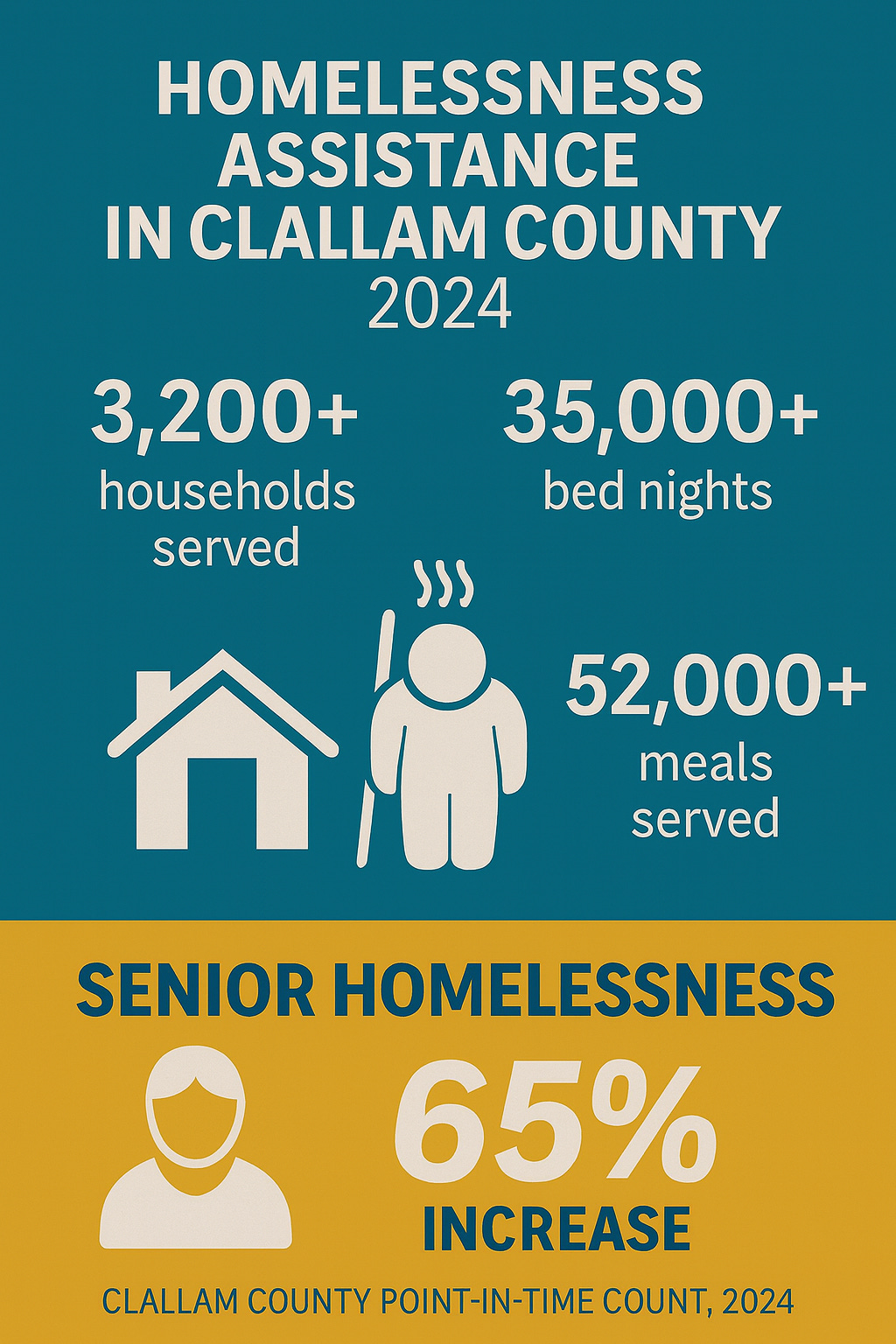

In the past year, Serenity House—the county’s largest housing and shelter provider—served more than 3,200 households across Clallam County. That figure includes families needing short-term rental help to avoid eviction, individuals in transitional housing, and guests in emergency shelters. The main shelter in Port Angeles alone provided over 35,000 bed nights to 634 unique guests, while its kitchen served more than 52,000 meals. Taken together, these numbers mean that nearly one in twenty county residents relied on some form of homeless assistance in 2024.

The people behind those numbers represent every demographic in our county. The majority of shelter guests are between 25 and 54 years old, but nearly one in five are seniors over 55. About 62% of clients identify as men and 36% as women, while a smaller number identify as non-binary or prefer not to answer. Roughly 6% identify as American Indian, Alaska Native, or Indigenous, reflecting Clallam’s tribal communities, while others identify as Black, Hispanic, or multiracial. Veterans, families with children, and young people aging out of foster care are also represented. Homelessness is not confined to one group, one age, or one neighborhood.

The annual Point-in-Time Count, a one-night survey of people experiencing homelessness, adds another layer to the picture. It showed a 33% increase in Clallam County’s unhoused population since 2021, with the steepest rise among people over the age of 55. Older adults who lose housing often face unique challenges: shelters and hospitals were never designed to provide long-term senior care, yet options like assisted living are usually out of reach without stable income.

At the other end of the spectrum, youth and young adults make up another vulnerable group. Serenity House’s youth department served 129 people between the ages of 12 and 24 last year. Many were leaving foster care, trying to continue education, or reentering the community after involvement with the justice system. Their paths look very different from those of older adults, but their basic challenge—finding safe and stable housing—is the same.

“Homelessness can cover a broad spectrum of people, but that essence of having that stable place of dwelling is kind of what I go by. A tent doesn’t constitute that.

Couch surfing doesn’t constitute that. It’s more than that.”

Joe DeScala - Founder of 4PA

And even these figures don’t capture the full picture. Many people live in what service providers call “hidden homelessness”—doubling up with relatives, sleeping in cars, or moving between friends’ couches without any stable place to call their own. Families with children are especially likely to fall into this category, as are young adults. Their circumstances often fall outside official definitions of homelessness, yet the instability and risk they face are just as real.

Capacity limits only deepen the challenge. The Port Angeles shelter has room for 152 people, but turnover is constant: guests leave, return, or cycle between temporary housing and the streets, not because services are ineffective, but because the broader supply of affordable housing falls so short. By mid-2024, the Clallam County Housing Authority’s waitlist had more than 2,400 people, while supportive housing programs like Dawn View Court had six applicants for every unit.

The ripple effects extend beyond shelters and housing programs. According to Port Angeles Police Department data, property crimes such as theft and vandalism made up more than half of all reported offenses in 2024, with substance use frequently a factor. Officers stress that most people without housing are not involved in crime, but a smaller group struggling with untreated addiction or severe mental illness accounts for a disproportionate share of incidents. That overlap creates visible disruption and puts additional pressure on both law enforcement and service providers.

Together, these numbers reveal a system stretched to its limits. Shelters, kitchens, and outreach programs are keeping thousands of people alive and connected to services each year. Yet the shortage of affordable units and supportive housing means too many residents remain stuck in limbo—unable to take the next step toward stability even when they’re ready.

Root Causes and Community Pressures

Behind the statistics are deeper forces shaping the homelessness crisis in Port Angeles. While every individual story is unique, several common threads appear again and again in the data, in service provider reports, and in conversations with local leaders.

At its core, homelessness in our community is being driven by two powerful and interwoven forces: the socio-economic pressures of housing costs, poverty, and an aging population, and the rise of substance use disorders—especially fentanyl—that destabilize lives and ripple through families, neighborhoods, and public safety systems. These drivers are not separate; they reinforce one another. Someone who loses a job or faces a rent increase may fall into housing instability; someone struggling with fentanyl addiction may lose employment or family support. When these pressures converge, the path back to stability becomes even more difficult.

Rising Housing Costs and Limited Supply

The most immediate driver is simple math: demand for affordable housing far outpaces supply. Clallam County added only a few hundred housing units between 2022 and 2024, a growth rate of less than one percent per year. Meanwhile, rents have risen faster than wages, and vacancy rates remain extremely low. The 2024 Coordinated Entry report shows that the median rent for a two-bedroom unit in Clallam County is $1,324, while the median renter household income is about $35,000 per year. At that level, a renter would need to spend over 45% of their income on housing, well above the 30% threshold considered affordable. For those living at or below minimum wage, the gap is even wider.

“It’s like musical chairs. If there are ten people and ten houses, everyone gets housed. But in our community, it’s more like three houses for ten people. Those with mental health, substance use, or physical disabilities often struggle the most to claim one of those limited seats.”

Wendy Sisk - CEO of Peninsula Behavioral Health

The result is long waitlists—more than 2,400 people countywide for subsidized or supportive housing as of mid-2024. Facilities like Dawn View Court see six applicants for every available unit. For many families, even a small disruption such as a missed paycheck or unexpected medical bill can be enough to trigger housing instability.

Mental Health and Addiction

Behavioral health remains one of the most pressing pressures connected to homelessness. Peninsula Behavioral Health, the county’s largest provider, ensures that people can begin care quickly, with weekly walk-in appointments available to start treatment without a long wait. This immediate access is an important lifeline for those reaching out for help.

Yet the deeper challenge is capacity. Services like detox support, inpatient treatment, and supportive housing are limited, and many people cycle between shelters, hospitals, and the streets because those longer-term resources aren’t available when needed. Substance use disorders—particularly fentanyl and methamphetamine—are a devastating driver of homelessness in Clallam County. These substances fuel personal instability, contribute to recurring health crises, and ripple into public safety challenges as individuals in crisis interact with law enforcement or emergency medical responders.

The result is not a lack of entry into care, but a shortage of the sustained treatment and recovery options that many people need to stabilize their lives. Without those supports, even those who want help often find themselves back in the same cycle.

Generational Cycles of Addiction and Trauma

Another factor that contributes to homelessness in Clallam County is the cycle of generational addiction and abuse. Service providers estimate that 15–20% of people experiencing homelessness come from households where substance use, trauma, and instability have persisted across multiple generations. These are often the hardest cases to break through, because addiction and trauma become environmental structures within a family.

This does not mean that change is impossible, but it does underscore the depth of the challenge. Breaking generational cycles requires more than emergency shelter or short-term treatment; it demands sustained support, trauma-informed care, and community-wide commitment over time.

An Aging Population

The sharp rise in older adults experiencing homelessness underscores another systemic challenge. The Point-in-Time Count revealed that seniors are the fastest-growing segment of the local unhoused population, increasing more than 65% since 2021. Once a person over 55 loses stable housing, their prospects narrow quickly. Physical health needs often outpace what shelters are designed to provide, and without sufficient income, traditional senior housing or assisted living is out of reach.

This trend is especially significant in Clallam County, where the population skews much older than the state overall. According to the U.S. Census, nearly one in three residents (32.5%) is age 65 or older, and almost half (48%) are 55 or older. This means that even small increases in housing costs or medical expenses can push large numbers of seniors into instability. When combined with the rise of fentanyl and other highly addictive substances—which do not spare older populations—the risks are magnified. Seniors who lose housing often face both economic pressures and health challenges at the same time, with very few options available for long-term stability.

Public Safety and Community Strain

Homelessness also intersects with community safety and well-being. Police data shows that property crimes account for more than half of reported offenses in Port Angeles, with substance use a common thread. While the majority of people experiencing homelessness are not engaged in crime, a smaller group battling severe addiction or untreated illness creates recurring incidents. This places added strain not only on law enforcement but also on emergency medical responders, courts, and neighborhood relations.

“There’s no property crime here that isn’t related to substance use. If you wanted to centralize your crime conversation, you’d talk about fentanyl—the people who sell it,

the people who are dealing it, and the people who steal for it.

That’s a much more accurate conversation than tying homelessness to crime.”

Chief Brian Smith - Port Angeles Police Department

Beyond the institutions, these pressures affect public perception. Visible encampments, repeat offenders, and strained services fuel frustration, mistrust, and fear. Service providers and volunteers often feel stretched thin, while residents struggle with how to balance compassion and accountability. These dynamics can polarize community dialogue—making it harder to focus on collaborative solutions.

Interconnected Root Causes

Taken together, these root causes show why homelessness is not simply the result of individual choices. It is shaped by systemic pressures—housing costs, health care access, an aging population, generational trauma, and the devastating impact of fentanyl and other addictive substances—all of which reinforce one another.

Economic strain can make a household vulnerable; substance use can compound that vulnerability; generational cycles of trauma can deepen it further. When public safety systems and community trust are also under strain, the path to stability becomes even steeper. Addressing homelessness therefore requires responses that acknowledge its interconnected nature, rather than isolating one factor at a time.

The Human Dimension

Behind every statistic is a person with a story. A senior who can no longer keep up with rent after the death of a spouse. A young adult leaving foster care without a family to fall back on. A worker who lost housing after an unexpected medical bill. A veteran coping with the long-term impacts of trauma.

“The causes for homelessness could be anything — a lost my job, a lost spouse,

a huge medical bill, or a domestic violence situation where it wasn’t safe to go back home.

For some people it is addiction, but for many it’s just ugly life circumstances.

I even have people in my shelter who go to work every day

but still can’t find an apartment they can afford.”

Sharon Maggard - Executive Director of Serenity House

Some stories reflect resilience in the face of short-term hardship. For example, a family with two small children entered the shelter after losing their home to an unexpected rent increase. With short-term rental assistance, they were able to stabilize and secure new housing within a few months. For them, the safety net worked exactly as intended—bridging a temporary gap and keeping the children out of prolonged homelessness.

Others illustrate the steep climb faced by those with layered challenges. One local man in his early sixties, coping with diabetes and limited mobility, entered the adult shelter after his caregiving spouse passed away. Without family nearby and with limited retirement income, he cycled between the shelter and hospital stays until eventually securing a place in supportive housing. His story shows how losing housing late in life can be devastating, and how complex the path to stability can be.

Youth and young adults bring yet another perspective. In 2024, more than 120 individuals between the ages of 12 and 24 sought help through Serenity House’s youth programs. Some were trying to finish high school while couch-surfing with friends, others were recently out of foster care, and a few were working their first jobs while sleeping in cars. Their needs often go beyond shelter: they require mentoring, access to education, and a sense of belonging to avoid long-term cycles of housing instability.

For some, homelessness is a brief chapter in a larger story. For others, it becomes a recurring struggle. People living with untreated mental illness or addiction often need supportive housing, wraparound services, and long-term recovery options before stability is possible. These layered needs explain why some guests cycle in and out of shelters repeatedly, not because they want to, but because the resources to make their next step permanent simply aren’t available.

The diversity of these experiences underscores an important truth: homelessness is not about “them,” it’s about “us.” It touches seniors on fixed incomes, young people trying to find their footing, families in crisis, and neighbors who once lived stably next door. In a county as small and interconnected as ours, the people experiencing homelessness are not strangers. They are members of our community.

Looking Ahead

The picture that emerges from the data and lived experiences is not simple. Homelessness in Port Angeles is shaped by a tangle of forces—economic pressures, addiction, generational trauma, and the realities of an aging community. Each of these on its own would be daunting; together, they create a challenge that touches nearly every corner of our county.

But naming these realities is not about resignation. It is about clarity. Only by understanding the scope of the problem can we begin to chart meaningful solutions. A clear-eyed view allows us to set aside easy answers or blame, and instead focus on approaches that meet the complexity of the challenge with equal depth and determination.

This first article has aimed to provide that foundation: who is affected, what the numbers show, and the pressures that drive instability. The next installments in this series will explore the helpers who meet these challenges every day, the obstacles they face within strained systems, the intersection of public safety and substance use, the generational cycles of trauma and addiction, and, ultimately, the solutions that are emerging to address homelessness in our community.

By following this journey together, we can move toward a fuller understanding—and toward the compassion, persistence, and cooperation that meaningful change will require.

An Invitation to Join the Conversation

I want to invite you to join in this conversation as we move through the series. Subscribe to stay connected, add your questions and reflections in the comments, and share these stories with others in our community. Whether you’re deeply committed to solving these problems, skeptical about the work being done, or simply curious to understand the issue more fully, your perspective matters here. I’m glad you’re part of this journey, and I look forward to taking the next steps together.

Active dialogue and engagement with our readers is crucial. Writers on this platform are encouraged—and expected—to revisit their articles regularly, responding thoughtfully to readers’ questions and concerns.

We want conversations, not shouting matches. Therefore, comments will be reviewed regularly and are expected to adhere to these foundational guidelines:

Stay on Topic: Comments must relate directly to the article.

Respectfulness: Every comment should demonstrate respect toward authors, website management, and fellow commenters. Bullying, name-calling, or disrespectful behaviors will not be tolerated.

Constructive Dialogue: Political grandstanding is unwelcome here. While some discussions naturally involve political elements, the goal is to enhance understanding, clarify perspectives, and contribute constructively.

No Personal Attacks: As Theodore Roosevelt wisely said, it's the person who is "actually in the arena" who deserves our respect. Criticism is welcome, but personal attacks are not.

Transparency: Any new guidelines needed as this platform evolves will prioritize civility, decency, and productive dialogue.

This is alot of information but, there is no total. Nobody can take this article and apply the statistics youve offered, to any number provided. "3200 families" "650 unique individuals" and more numbers appear but dont correlate. The PIT survey used to provide a total estimated "unhoused" why is that number not here? It seems that this piece conflates a very, very broad range of needs across a large demographic and seeks to collect it into one message or one crisis. How many are employed? How many are addicted? How many are suffering form non-addicrion mental health crisis? How many are local, long time residents now unfocused? How many are new residents? You should know where im going witn this. A 33% increase since 2021 does not communicate anything without a starting figure and a current figure, demographics and origin/time in the county to make it make sense. If that increase is a result of unhoused migration to Clallam or layoffs or kicked out of home youth or???

Most folks who will read this now graduated from high-school and have post secondary education. They can handle details. People are tired of summaries and stats, they want to know the details to better undersnd AND frankly, to give Buy-in if it is deserved.